Watch this video for a detailed description of what the CCL is and why it gets injured in dogs.

Read this article to learn about surgery for CCL disease.

CCL Overview (Similar to the ACL in Humans!)

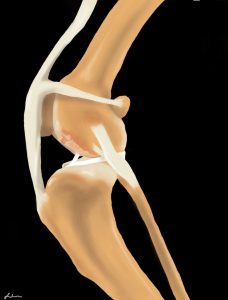

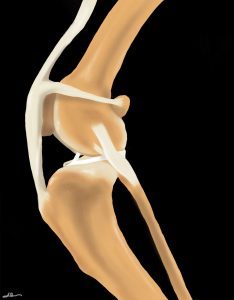

The cranial cruciate ligament (known as the anterior cruciate ligament or ACL in people) is one of several ligaments in the stifle (knee) that connect the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone). The CCL has 3 main functions:

- Prevent the tibia from sliding forward in relation to the femur

- Prevent the stifle from hyperextending

- Prevent the tibia from internally rotating

DID YOU KNOW: CCL disease (rupture) is the most common causes of hind limb lameness in middle-aged dogs. The average age of dogs tearing their CCL is 7 years old, but it can occur in any age or size dog. If your dog is limping on their back leg, it is important to rule out CCL disease and not assume the limp is due to hip arthritis.

This article covers why the CCL becomes damaged, what signs to look for if your dog has a CCL disease, and how your veterinarian will diagnose CCL disease.

Why does the CCL rupture?

In people, the ACL typically ruptures as the result of an acute injury, often related to sports. However, in dogs, CCL sprain is rarely the result of a traumatic injury.

Rather, dogs tend to experience CCL “disease,” meaning that the ligament degenerates or weakens over time due to genetic, conformational, and/or immune-mediated processes within the joint.

It is believed that mild inflammation, or synovitis, is present in the stifle joint prior to the CCL actually tearing. The ultimate cause of CCL disease is not fully understood but is the subject of a lot of research among veterinary scientists.

There are risk factors for CCL sprain, including:

- Certain breeds (Labrador Retriever, Newfoundland, Boxer, Rottweiler, Pit Bull, English Bulldog, Westie)

- Being overweight or obese

- Medial Patella Luxation (MPL)

- Being spayed or neutered (this is a complicated topic and we are continuing to learn more. It was recently found that age of spay/neuter was specifically associated with CCL disease in Labradors: the risk of CCL disease increased over 11 times in dogs spayed/ neutered before 12 months (DeForge T, et al. JAVMA 2025). Correlation has been observed in other breeds as well. Please read our accompanying article to learn more.)

The weakened CCL is at risk for damage or “sprain.” A sprain can be divided into 3 grades:

- Grade 1: stretching of the ligament without tearing; the ligament does not function normally and may be painful

- Grade 2: partial tearing or rupture of the ligament; this leads to mild instability of the joint

- Grade 3: complete rupture of the ligament with more significant instability of the joint

The degree of CCL damage can progress from Grade 1-3 sprain over days to years.

CCL sprains will lead to progressive arthritis in the stifle joint.

Typically, dogs with weak CCLs will have a mild sprain at first, then partially or completely rupture the ligament following vigorous activities such as running or jumping. Unfortunately, the condition that causes CCL disease is often present in both stifles, and about 50% of dogs will rupture both CCLs within 1-2 years of each other.

CCL disease is one of the most common orthopedic conditions seen in dogs, and CCL surgery is the most common orthopedic surgery performed by veterinary surgeons.

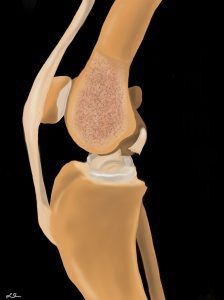

Are any other parts of the joint affected when the CCL tears?

Quite often, yes. The medial and lateral menisci are fibrous pads attached to the top of the tibia that provides added stability to the stifle. The medial meniscus is often injured after CCL rupture (Grade 2 or 3 sprains).

Without the support of the CCL, the femur puts abnormal pressure on the medial meniscus, which can lead to tearing.

What signs will I see if my dog has CCL disease?

CCL sprains will lead to varying degrees of lameness, depending on how much damage to the CCL is present and how quickly the damage occurs. No matter what degree of sprain has occurred, there will be inflammation in the stifle joint and likely some degree of pain.

The most common scenarios that can occur with CCL sprain:

- Acute rupture (Usually Grade 3)

- Chronic rupture (Grade 2 or 3)

- Partial tears (Grade 1 or 2)

Acute Rupture:

This means that the ligament sustains severe tearing all at once. This is actually the least common type of CCL rupture.

Following an acute rupture, your dog won’t want to bear weight on the effected leg. The lameness will likely improve over the next several weeks; however, if it suddenly gets worse, it could indicate that the medial meniscus has become damaged. At that point, your dog will not return to normal function without some evidence of lameness.

Audible clicking or popping may be heard if the meniscus is torn. It’s rare but possible for dogs to have acute ruptures of the CCLs in both hind limbs. But if this happens, it could result in your dog not being able to stand up with their back legs and they may appear paralyzed (but they aren’t!).

Chronic Rupture:

With chronic CCLR, you may not recall a specific incident that triggered lameness, but you will notice waxing and waning limping over weeks to months.

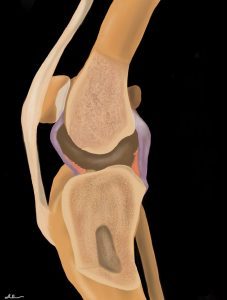

Over time, the body tries to stabilize the knee by surrounding the joint with scar tissue. This will look like a swollen knee and your dog’s range of motion in the limb might be compromised. Arthritis will develop inside of the joint as a result of this chronic instability.

Typically, dogs can still bear weight with chronic CCLR, but lameness gets worse after exercise or activity.

Partial CCL ruptures (Grade 1, 2 sprain)

These are less obvious, but they are a common type of injury.

Your dog may appear lame with exercise but improves with rest. However, the ligament will continue to weaken and the joint will become increasingly unstable. Eventually, the ligament will likely rupture completely and lameness will not resolve with rest.

How will a veterinarian diagnose CCL sprain or rupture?

The first part of your veterinarian’s exam will consist of learning the history of your dog’s lameness. They will ask if there was a known trauma and if anything has helped resolve the lameness.

Then, they will watch your dog walk and move around the exam room in order to characterize their degree of lameness. Importantly, some dogs will “hide” their lameness when at the vet due to increased adrenaline. Your vet will use additional exam techniques and clues that point toward a diagnosis of CCL sprain.

One test that your vet should do is watch how your dog sits. If he sits on one hip, with the other leg held somewhat out to the side, this is called a “positive sit test.” This is not 100% diagnostic for CCL sprain, but if you have noticed that your dog has recently been sitting this way, as opposed to symmetrically with both knees bent at their side, there is a very good chance they have a CCL sprain.

Other tests your veterinarian might do

Next, your veterinarian will palpate your dog, including the knee (stifle) of concern. The first sign of an early CCL sprain is discomfort with full extension of the stifle and/or full flexion. One of the jobs of the CCL is to prevent hyperextension (over-straightening) of the stifle, so if force is applied that starts to stress the ligament in a way that it is not able to resist fully, the body reacts by pulling back since it knows the ligament is not fully functional.

Other signs of CCL sprain are muscle atrophy, swelling inside the stifle joint, known as joint effusion, and firm swelling surrounding the stifle, known as a medial buttress.

The hallmark of a CCL rupture is palpation of instability in the stifle joint using the “cranial drawer” and/ or “cranial tibial thrust” tests. In order to feel this, your dog may be placed on his/ her side or remain in a standing position, and your veterinarian will feel the stifle for abnormal motion. If either of these tests is positive, they will make a diagnosis of a CCL tear (either a Grade 2 or 3 sprain).

Testing for “cranial drawer”

Testing for cranial drawer or tibial thrust is not usually painful; however, some dogs might be too tense or nervous to allow a thorough exam. If this is the case, your veterinarian might recommend giving your dog a sedative to complete the examination.

Patients with chronic ruptures associated with a large amount of scar tissue and arthritis may not exhibit cranial drawer, but they still have CCL disease.

Your veterinarian will also likely order X-rays to rule out other potential causes of hind-limb lameness and to evaluate the extent of arthritis within the joint.

What is the role of x-rays? Does my dog need an MRI?

The CCL dose not show up on x-rays, but secondary signs of CCL sprain/ rupture do show up. These include increased fluid in the joint (effusion), arthritic changes, and abnormal positioning of the femur and tibia (the tibia is shifted forward) due to the CCL not functioning. These changes, along with clinical signs and history are sufficient to make the recommendation to proceed to surgery.

In rare cases, dogs may have a clinical history +/- clinical signs that are suggestive of CCL disease, but the x-rays do not show any evidence of joint disease. In these cases your veterinarian or veterinary surgeon might recommend additional tests to look for other causes of limping. In very rare cases, MRI might be recommended, but it is not typically part of the work-up for CCL disease.

See this article to learn about surgery for CCL disease.

Article written by Dr. Kristin Shaw

Reviewed and updated: 3/2025

Illustrations by Stephanie Erdesz