What does arthritis mean for my dog?

Dogs, like their caregivers, can develop arthritis in any of their joints. Recent research shows that 40% of dogs under the age of 4 years old have evidence of arthritis on x-rays, and about half of these dogs show symptoms of pain associated with arthritis. Dogs almost always develop secondary osteoarthritis, meaning there is an underlying developmental problem or trauma to the joint that causes arthritis to set in. Unfortunately, most dogs aren’t diagnosed with arthritis until they are 8-10 years old, at which point it may actually be harder to control the symptoms of arthritis compared to recognizing and treating it early.

Arthritis can be challenging to diagnose early on, and the signs that our dogs are uncomfortable can be subtle if we don’t know what to look for.

Diagnosing and treating arthritis from the earliest stages is one of the best ways we can keep our dogs active, happy, and comfortable for as long as possible.

You can help your dog have a better quality of life by making some simple changes to their daily routine. In this article, we’ll cover what arthritis is, what causes it, and how veterinarians diagnose it. In other sections of CARE, you’ll learn about the different options available to help your dog enjoy a healthy, active life for as long as possible.

What is arthritis?

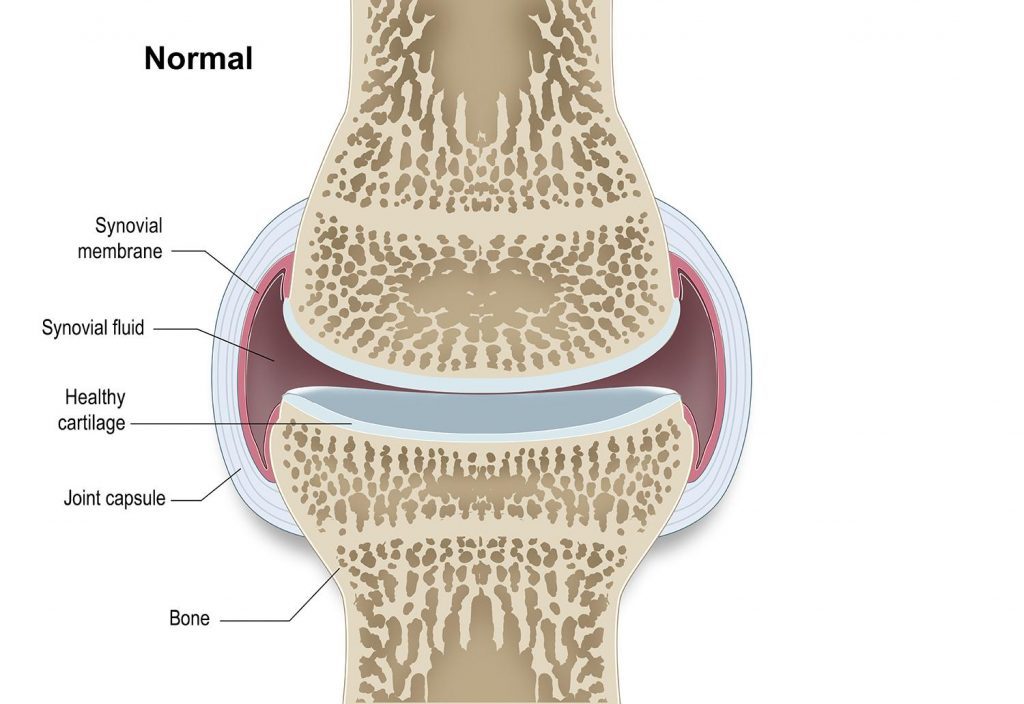

A joint is where two (or sometimes three or more) bones meet in the body; joints allow movement of the body in all of the ways we normally expect.

Arthritis, in the simplest terms, is inflammation of the joint with secondary changes that lead to pain and reduced joint movement.

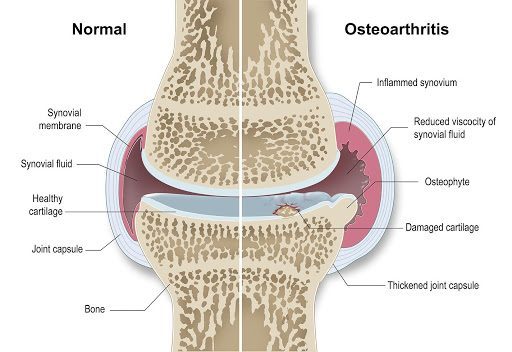

Cartilage lines the end of the bone at the joint, and joint fluid fills the small space between the joints. In a normal joint, cartilage is smooth and slippery and allows the two bones to move back and forth without friction. Normal joint fluid is sticky and provides lubrication to the joint.

With arthritis, the cartilage gets thinner and starts to break down. This is what leads to a vicious cycle of inflammation, joint swelling, thickening of tissue around the joint, further wearing away of cartilage, and ultimately stiffness, muscle atrophy, and pain.

See the differences below?

Types of arthritis that dogs get

There are several different types of arthritis, but the most common kind in dogs and cats is osteoarthritis (OA), also called degenerative joint disease (DJD), which develops secondary to:

- Joint instability

- Joint incongruity

- Osteochondrosis/ OCD (a cartilage flap; can occur in the shoulder, elbow, stifle and tarsus)

- Trauma (example: a fracture that involves the joint)

How will my veterinarian diagnose arthritis in my dog?

Your veterinarian may suspect arthritis based on symptoms of pain and reduced mobility and physical examination. Then, the most common way to confirm the diagnosis arthritis is with an x-ray (also called radiograph). X-rays indicate joint swelling or changes to the bone, such as thickening or bone spurs.

Sedation is strongly recommended for obtaining x-rays because your dog will need to lay perfectly still on a table so that a clear image is taken. Sedation reduces the stress and discomfort associated with this procedure. Some dogs might actually be more painful after x-rays due to manipulation of the joint.

X-rays don’t show all of the structures in the joint that are effected by arthritis. The best way to check the condition of your dog’s cartilage and synovium is through surgery, either by inserting a small camera into the joint (arthroscopy) or by surgically opening the joint (arthrotomy).

These procedures require full anesthesia and may be both diagnostic and therapeutic, depending on the procedure performed.

Other diagnostic tools

If your dog has significant joint swelling, your veterinarian might recommend a joint tap to assess the joint fluid. This is usually recommended if your veterinarian suspects your dog might have an infection or an autoimmune condition.

To determine the underlying cause of arthritis, pain or lameness, your veterinarian might recommend doing a CT scan or an MRI. This better allows your veterinarian to assess the bone and surrounding tissues.

CT scans are usually recommended for issues with the elbow, tarsus (hock/ ankle), and carpus (wrist), and MRIs are used more often for issues with the shoulders, stifles (knees) and back. Full anesthesia is required for both CT and MRI.

Can arthritis be cured?

Unfortunately, arthritis is an incurable disease in both animals and people. But there’s hope! There are many effective therapies that will help you and your veterinarian manage your dog’s arthritis for a long time.

There are both surgical and non-surgical treatments available that you should discuss with your veterinarian.

In some cases, surgery might be recommended at initial diagnosis if it may slow the progression of arthritis. This is often the case with cruciate ligament tears, which is similar to an ACL tear in a person.

For dogs that have hip or elbow dysplasia, your veterinarian will likely recommend a multi-modal approach to treatment that could include:

- Pain management

- Weight loss and a nutritional plan

- Regular, low-impact exercise

- Omega 3 fatty acids

- Supplements to protect your dog’s cartilage

- Physical rehabilitation and therapeutic modalities

- Surgery

- Intra-articular injections

- Acupuncture and other complementary therapies

CARE will cover each of these topics in separate articles to help you manage your dog’s arthritis and keep them active and happy.

Reviewed/updated 12/2024